How to turn boring research into engaging content

Research shows that using research in a presentation makes it more likely you will be believed. It boosts your credibility in the mind of the listener and makes your persuasion more compelling.

The problem is that facts, stats and figures can be very dry and snooze-inducing. They are also easily forgotten. Anyone who has sat through slide after slide of bar graphs, diagrams and pie charts knows this well.

In this way, research and the data they produce can easily bore your audience and have the opposite effect on your effectiveness when not done right. Not to mention being forgotten almost instantly.

Therefore in this article, I will show you three areas of your supporting research you can look into when developing your presentation to turn boring copy into engaging, memorable and persuasive content.

The Researcher

The people who conduct research are sometimes just as intriguing and even moreso than their research.The lives of some of these people are so interesting that it would almost be a crime not to talk about them.Often there are fascinating backstories to how they came about the research that you are using. Science journalists know this, perhaps because they talk to a lot of researchers. Just pick up any issue of a popular science magazine or book and you will see this approach to writing on display with spell-like engagement in close tow.

The people who conduct research are sometimes just as intriguing and even moreso than their research.

You can use the same technique in your speaking when discussing research. This can make your presentation a lot more interesting.

Consider the example below:

Research conducted in Sydney by Dr Miso Smat indicates that bacteria living in our armpits might hold the key to curing halitosis (bad breath)

Not bad right? Clear, succinct and straight to the point. Except that it is also quite boring.

By the way, as a public service announcement, that example is pure fiction.

Now consider this alternative.

Dr Miso Smat or Mister Miso as he is affectionately called by his mother has always been fascinated with the human body. As a boy of just 8 years old, he would collect hair samples from his friends – a request that must have raised many eyebrows – and try to create clones from them. Perhaps so that he could have twice as much fun playing soccer – his favourite sport. However, it would not be until several decades later, 4 to be exact, that Mister Miso, now Dr M Smat, would conduct research leading to a discovery that links two very unlikely parts of the body together in a most unlikely and interesting way….

Still pure fiction.

If you were in the audience, which one would have you more engaged? Sure, the first might arouse your curiosity but it is likely the second that will get you really invested in the content.

This is one way you can make the research you quote in your presentations more engaging. Find out and talk about the researcher(s) lives especially as it relates to the research you are discussing.But don’t fret if the researcher’s backstory is nothing to write home about.

There are other areas you can look at.

The Research

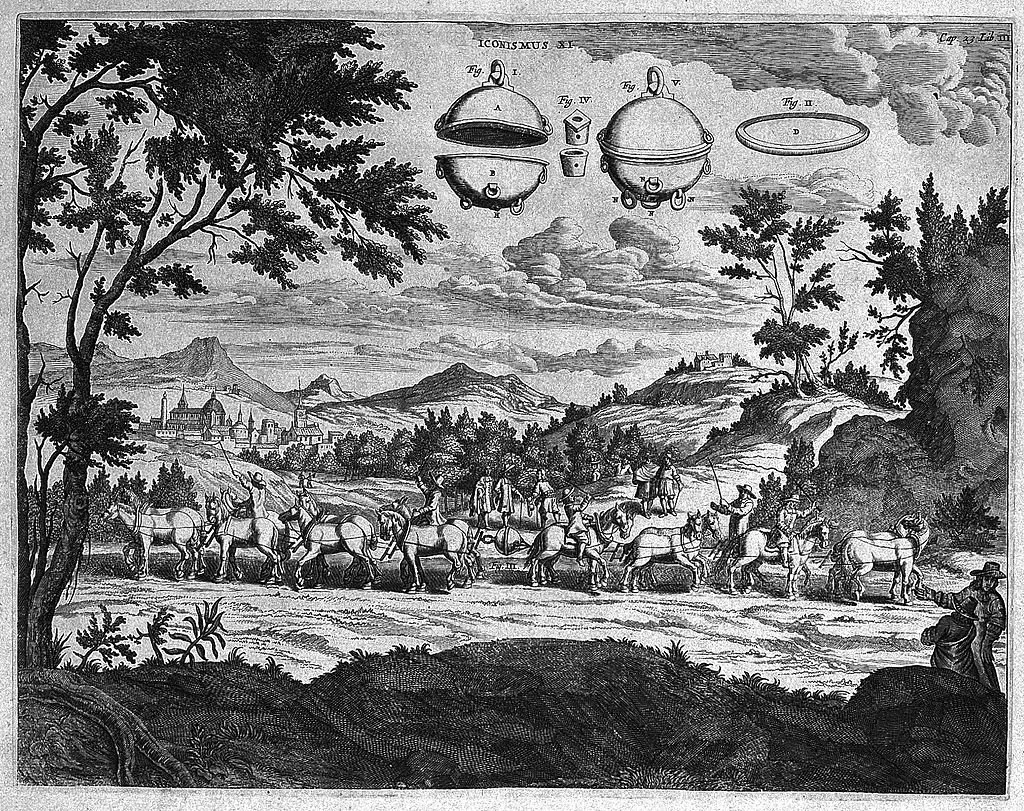

You likely have heard about Pavlov’s salivating dog and Otto von Guericke’s 8 horses. Ok maybe you don’t know about the second one but it’s worth learning about.

In any case, both these experiments are still talked about today several decades and centuries later, in part, because the experiments themselves are extremely interesting.In recent times, scientific inquiry has become more and more ambitious and, depending on your subject, there are probably some interesting experiments sitting innocuously under the Materials and Methods heading of the research paper you are perusing.

If this is something you feel your audience will enjoy, understand and appreciate, by all means, add it in and make it into a neat story. For an example of this technique in action, read this post.

...there are probably some interesting experiments sitting innocuously under the Materials and Methods heading of the research paper you are perusing.

The main point: research experiments can read like sagas… if you find the right ones and read them right. When you do this, you can begin to piece together a compelling story.

This brings us to the next point.

The story

All research and all data would be useless if they did not show us something. That is, if they did not reveal to us some perspective of reality.Or simply put, if they do not tell us a story.The problem is that many speakers are too busy memorizing statistics and journal titles and publication dates to dig deep into what the story is. What is the research or data actually suggesting?

What is the research or data actually suggesting?

You don’t have to be a statistician or have a PhD in the field, but you do need some critical thinking. If you are speaking on the subject at all, I assume you know something about it and can draw defensible conclusions.

The real fun is when you turn all of that into a story.

Here is a true-life example from a client of mine who needed coaching on speaking about a sensitive issue at a professional symposium. The human groups affected have been replaced with furry rodents not just because it protects the identities of those involved, but because its just more fun!

Here are the statistics my client had:

95% of victims of carrot theft are pink bunnies. It is estimated that only 5% of carrot thefts affecting pink bunnies are reported to the raccoon task force.

What is the story?

Pink bunnies are being robbed of their carrots and, for some reason, they are not reporting it to the raccoons. They are not squealing up!

You will see right away that there is a wealth of insights that can be teased out of this story. And, like is typical of useful data, it provides good questions as much as good answers. Are the bunnies afraid? What are they afraid of? What happened to the few that went to the raccoons? How can we solve this? Etc.

...never ignore the story. The story is the point.

The point is, data and research tell a story. Find out what the story is and tell it using the data.

Make the story the star and the data the supporting actor. Not the other way around.

When talking to a very intellectually advanced and accomplished audience, you may lean into the data a bit more. But never ignore the story. The story is the point.

Riveting research

Now you have three more tools to add to your persuasive toolbox. Pull these out when using research and data to support your points and you will be able to reap the double benefit of credibility and audience engagement with your ideas and content.

It will also help the audience remember what you had to say - a very important factor in making a lasting impression.

Until the next post, speak with skill.